The Conservative Shadow Lord Chancellor, Robert Jenrick, has raised his concerns about lenient sentencing of those convicted of the rape and exploitation of children. In a Twitter/X post he wrote:

A queue of men awaiting their turn to rape a child. Bradford Crown Court's answer? 6 years. Out on licence in 4. This is not justice.

The court's reasoning was shocking: One rapist got a reduced sentence because he's now "very, very different" and "involved with his local mosque." How does being involved in your local mosque reduce your sentence for child rape? This isn't just weak sentencing. It's dangerous naivety.

Jenrick doesn’t name-check the judge in the case - Ahmed Nadim. He has an interesting background.

Further details of the case can be found here. Jenrick does not mention another shocking fact - that out of the three convicted, two have actually absconded during the trial. Only Ibrar Hussain - who Jenrick refers to above, sentenced to six and a half years - will actually start that sentence. Judge Nadim is quoted as saying: "The message must go out loud and clear that the criminal justice system will do all it can to protect young and vulnerable members of our community." Neither the length of sentences, nor the laxity around two of the defendants, would seem to bear out his words.

Nadim has something of a history of lenient sentencing, particularly around sexual abuse cases. These include:

Five years for raping a child

21 months for raping an underage schoolgirl

No custodial sentence at all for making indecent images of children as young as five. Nadim states “There was evidence that you explore your sexuality in a way that is outside the norms of society. It is disappointing that a man of your age and your experience of life behaves in this manner.”

No custodial sentence for “attacking a ‘secret’ partner in a drug-fuelled rage”. (The phase ‘secret partner’ is concerning.)

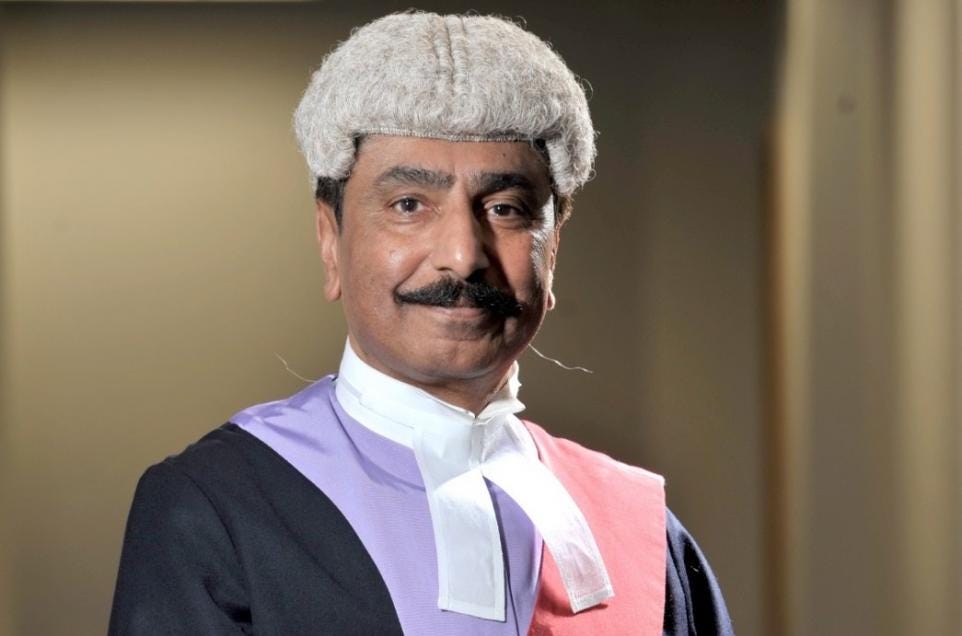

Nadim was appointed as circuit judge for Bradford Crown Court on 2020. Born in Pakistan, he came to the UK at the age of 13 unable to speak English. He is the model of the successful immigrant; well spoken and even slightly dapper, he was included as one of eight “A day in the life of a judge" series publicised on the UK Judiciary website (coinciding, of course, with South Asian Heritage Month.)

Prior to the bench, Nadim had a successful career at the Bar. His profile at Lincoln House Chambers states:

Due to his particular skill in cross-examining vulnerable witnesses and detailed preparation of cases involving large amounts of papers/information, he has been instructed in virtually all the major cases resulting from CSE/grooming investigations.

(Emphasis mine.) It also highlights some of his recent cases:

R v NH – Successfully defended allegations of immigration fraud

R v LMC – Successfully defended a military officer accused of multiple acts of rape of a German national before the Court Martial, sitting in Germany

R v MA – Defeated the Prosecution’s application to adduce hearsay evidence of a complainant in a CSE case where the defendant was accused of multiple allegations of rape. This resulted in the Accused being exonerated of the most serious allegations made against him.

R v M.A.G. – Successfully appealed convictions in respect of Tax and VAT fraud offence before the Court of Appeal

Here, he is stated also to have been on the defence of “grooming” gangs in the Rochdale and Manchester areas. He has also been involved in defending fraud cases, immigration and trafficking offences, and the 2001 Bradford and Oldham riots.

Of course, the presumption of innocence and legal representation in court are pillars of the English legal system, surviving even the reforms of the Blair era. Even mass rapists need representation, unpalatable though it may be. Nadim was doing his job, and doing it well, it seems. But you can’t win them all: one appeal that failed, Nadim argued that a “sentence of eight-and-a-half years for rape and sexual activity with a child was ‘in excess of his culpability’ and ‘disproportionate’ as he did not know she was a vulnerable victim.”

Also concerning is something he highlights in the video linked above: "It is important that the criminal justice system reaches out to the community so that the community is more informed..." What he means by this is not immediately clear, but may perhaps relate to something else he has referred to here. “Since his term in office he has only seen two people from the Asian community attending jury service, adding that the community needs to take more responsibility in playing its part in the British justice system."

This is not surprising in itself and in line with standard “representation” rhetoric, calling for more Asian representation on juries (which tend, for reasons of practicality, to be kept local.)

All this fits in with the concept of milletisation I have referred to before: Nadim is arguing for a much larger role for the “community” to be more responsible for trying and sentencing itself. I am reminded of what I have previously written about Nazir Afzal, and his argument for “the policing of ‘communities’ (primarily) within themselves; what I have called the milletisation model (the Ottoman system whereby different religious communities managed their own internal affairs separately).”

For all these concerns about Nadim’s sentencing leniency that are being raised, there is an issue in his past which has, remarkably, been memory-holed. Nadim stood trial for money-laundering in 2006 alongside his brother-in-law Asad Chohan. Chohan was convicted; Nadim acquitted. Also convicted were his brother, Saajid Chohan and the family book-keeper Mohammed Ilyas, both of whom were jailed. Nadim’s sister Samiah - Chohan’s wife - was also convicted of money laundering but escaped jail.

As this article describes it: “A BIRMINGHAM crook behind a £185 million criminal empire has been told to repay almost £30 million under Britain's biggest-ever confiscation order.” (Nadim is described as a “judge” here, which is not strictly accurate, but he had been appointed as a recorder in 2004, described as “the first step on the judicial ladder.”)

Chohan had previously been convicted in April 2001 of conspiracy to avoid excise duty over a large quantity of tobacco. He was sentenced to 18 months' imprisonment.

Chohan fled the country before the fraud trial and was on the run for over 11 years, initially in Pakistan, then Dubai until he was finally caught in Canada in 2018. He is now serving a 12 year sentence and must repay £53 million.

Some further details may be gleaned from the (unsuccessful) appeal by his sister against the verdict:

On 6th December 2001 he transferred the matrimonial home at 267 Wake Green Road for £158,000 to Nadim, the appellant’s brother, on behalf of the appellant [his sister]. Nadim was a barrister who practised in Manchester and lived in Rochdale. The transfer had been made to him because no lender would lend to the appellant.

The appellant and Nadim had been charged with money laundering in respect of 267 Wake Green Road, in that it was said that the sale to Nadim was an arrangement which facilitated the retention or control by Asad Chohan of the property and that property represented the proceeds of Asad Chohan's criminal conduct, which both were said to know.

There was a long trial, lasting some 30 days, at Birmingham Crown Court before His Honour Judge Griffith-Jones and the jury during October and November 2006. The retirement of the jury was about five days. Nadim was acquitted but the appellant was convicted by a majority of ten to two. She received a sentence of 80 hours' community service. She sought leave to appeal on three grounds. She was granted leave on one, namely the conviction was unsafe as the jury's verdicts were inconsistent. This is not a case where there were inconsistencies between verdicts on different counts but it is said that, if the jury had acquitted Nadim, they should also have acquitted the appellant.

The appeal was dismissed; it was held that “it cannot be argued that it was perverse or irrational” for the jury to reach differing views on the knowledge of Nadim and his sister.

For the avoidance of doubt, Nadim was acquitted in the original trial and there is no reason for him not to have continued his career, or be appointed as a judge. And we certainly should not be held responsible, morally let alone legally, for the actions of our relatives.

But we must hope that those who judge us themselves have good judgement. And that those convicted of some of the worst crimes that we can imagine pay an appropriate price.

Thanks so much for this really interesting piece. We know so little of those that sit in judgement on us.

When I was a very young child, there was a series on ITV in the afternoons (when afternoon tv was surprisingly high quality) called Crown Court. It portrayed the judges and barristers as arbiters of justice - well spoken, highly educated people. The ‘crème de la crème’ as Miss Jean Brodie would have said. No doubt, in reality, they had their foibles but one could hope they were better than the people in the dock.

But nowadays we have miscreants like the gentleman you describe Mat, sitting in judgement on English people. It really is an indictment on how far British society has fallen.