A Tale of Nostalgia and Nepotism

Sam Dalrymple's 'Shattered Lands' has been lauded universally - but why?

It’s hard to find a debut work that has been received as highly as Sam Dalrymple’s ‘Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia’. I’ve not seen a review that’s less than laudatory: ‘Sparkling… Stunning achievement… Vivid… Essential and irresistible reading…’ ‘It is astonishing that this story has not been told before.’ My first reaction to a review was ‘This book sounds so awful I might have to read it.’ So I did, and I was right.

Sam is the son of William Dalrymple, popular author on all things Indian, Delhi-resident and the bringer of the Literary Festival to India (Jaipur). He’s a good writer; if of a distinctly leftist bent; I’ve read most of his books. Sam describes himself as ‘writer, film-maker and peace activist.’ He spent some time in Afghanistan with Turquoise Mountain Foundation, the taxpayer-funded NGO run by Mrs Rory Stewart; although it’s not known whether he was involved with the farcical initiative of lecturing bemused Afghan women on Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Fountain.’

Writer, film-maker and peace activist Sam Dalrymple

As an undergraduate at Oxford, Dalrymple (with a couple of associates) set up his Project Dastaan, a ‘peace-building initiative which examines the human impact of global migration through the lens of the largest forced migration in recorded history, the 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan.’ Also funded partially by the taxpayer (through the British Council and Arts Council, as well as the National Lottery), this is a modernised, digital (and virtual) ‘oral history’ project which seeks to ‘immortalise the experiences of the Partition generation and create a lasting impact between generations old and young.’ ‘Partition Tourism’ has been raised as an opportunity, as long as it does not have a ‘nationalist narrative that explains what happened in 250 words.’ He is also happy to present himself as a ‘Turkish expert’, guiding tourists around Armenian sites now in Turkey for a high-end travel company. Nice work, if you don’t mind whitewashing genocide.

He seems to have signed the deal to publish ‘Shattered Lands’ five years ago, when he was barely out of university, with HarperCollins, the second-largest publisher in the world. Quite a coup for a fresh-faced Oxford grad, even one well connected; possibly the most significant since Douglas Murray had a book on ‘Bosie’ (Wilde’s homosexual friend) published when still an undergraduate1. It’s a lavish tome, superbly illustrated, and abundant with maps; even if the latter are sometimes badly chosen (I suspect the casual reader would find it more useful to have a detailed map of the borders of the princely states of Junagadh or Hyderabad, rather than tracking Gandhi’s meanderings, which are secondary to the text.)

Dalrymple has a Big Idea, and a Method. The Big Idea is the ‘Five Partitions’ of the subtitle, namely the partitions of what I would call the ‘Legalistic Raj’ extant in the early twentieth century:

The administrative separation of Burma in 1937

The administrative separation of Aden from the Raj in 1937, and the subsequent separation of the other Gulf States by 1947

The partition of India and Pakistan on independence from Britain in 1947 (Dalrymple calls this the Great Partition)

The fate of the princely states (absorption into India or Pakistan) around 1947

The war of 1971 in which Bangladesh won independence from Pakistan

The Method is a standard narrative-history heavy on the sort of bottom-up oral history he champions in Project Dastaan; memoirs, published and unpublished, references from other sources, and (for more recent events) his own interviews. The goal is to search for authenticity, and the ‘luminous detail’. The problem is that the author is very hit-and miss in his curation. A first-hand account can, of course, be a wonderful corrective to received history, but this is rare; most people’s voices are just noise, and a liberal ‘everyone’s voice must be heard’ attitude is apparent.

There are gems, of course, such as Sarojini Naidu’s observations - but then, she was a confidante of the key players of independence, Nehru in particular. There’s a wonderful passage when the Burmese independence fighter Bo Maw is sprung from his British gaolers by his wife and a couple of conspirators by the means of demonically strong Naga ghost chillies. ‘Are we cooking something?’ asked Maw. The prison cook roasts the beasts, creating an eye-blinding smoke under the cover of which the prisoner effected his escape.

But the contributions are more often pedestrian, and make the book less serious. An example: several pages are devoted to the Japanese invasion of Burma, and we sit through:

Donald Menezes recalled that ‘after the initial panic, people relaxed and began moving in the streets, as in the usual practice alerts’… ‘People who were standing in the street and watching the planes [were] machine-gunned or blown to bits along with buildings.’

‘The spare bedrooms were allocated’ remembered Eric, ‘and all was cosy with a sense of safety that comes in numbers’… The streets were empty except for howling street dogs and Lady Gorman-Smith, the governor’s wife, who was charging around trying to raise moral.2

I have no idea if the author thinks that passages such as this have any value; but he is someone who is happy to write such trite statements as ‘War on the front line was brutal’, and ‘Donald hid in his trench with his family and servants for what seemed like an eternity.’3

Dalrymple knows his audience, though, and it’s the middle class Brit. At every point where there is an animal story to be brought in, he does so: from the street dogs quoted above, to ducks speaking Arabic and pet mongooses, to quoting at length the legends of the dogs of the Nawab of Junagadh (including the ‘marriage’ of Roshana to British Labrador Bobby, both atop elephants) before debunking it with some sadness.

Associated with this is a revisionism of the princely states more generally, as beacons of culture and syncretism drawn in contrast to the nationalisms of the emergent Pakistan and India. ‘Partition’, in Dalrymple’s terms, is negative, even if presented as ‘complex’, unlike the simplistic evil of ‘nationalism’. His Raj is more of a south Asian idealistic proto-United Nations than a project of power and money; an ‘Imagine’ imagined by George Harrison rather than John Lennon.

If the Method of the book is not ideal, the Big Idea had better hold. I don’t believe it is at all convincing.

Dalrymple is best in my opinion on his ‘first partition’, that of Burma (although this may be simply that this is the topic about which I know least). He makes a convincing case that Burma was economically integrated into the Indian Empire prior to 1937; the Rangoon Boom was real, and that its separation hit the colony hard. It is also undoubtedly true that the border between Burma and what is now the Indian north-east was drawn with scant reference to the tribes on the ground - he makes much of the Nagas and their leader Phizo, split between the two, and their subsequent struggles.

A constantly recurring refrain is the ‘nationalist’ ‘sacred land of Bharat’, presented as a Hindu-centric exclusionary project; and Burma of course is not part of this. (It’s worth noting that neither is the Indian history, trade, culture and diaspora of the rest of south-east Asia. Different fates of conquest and legislation could have included them in the ‘Raj’ just as easily.)

It’s probably true that the administrators of the 1930s, had they known what was to happen a decade later, may have drawn the boundaries differently; but it’s hard to believe that this would have involved more, not fewer ‘partitions’. Ethnically, religiously and linguistically complex mountainous terrain such as the border between modern India and Burma have a tendency to be fractious. Trying to pretend that administrative legalism - the fact that Burma had been ruled as part of the Raj - would trump in-group interests, notwithstanding ethnically Indian economic interests, is woefully hopeful. In fact, Dalrymple directs his reader to the economic realities that led to the Burmese uprising of the 1930s: in the wake of the 1929 crash, the (Tamil, Indian) Chettiar money-lenders had increased their ownership of agricultural land from 6% (in 1930) to a quarter. He notes that Burmese media had praised Hitler’s treatment of the Jews, without drawing the parallel.

The ‘second partition’ - removing the British Arab possessions of Arabia, from Oman to Kuwait, is possibly the weakest. Trade across the Arabian Sea was of course real, but cultural influence from the subcontinent never did head west in the way that it did east (we speak of Indo-China, but never Indo-Arabia). Dalrymple (for a ‘historian’) has a tendency to be trapped in a moment (in this case, the Raj of the early-mid twentieth century) with a strange blindness to the wider history. The defence of the sea routes to India after the construction of the Suez Canal was vital to the Empire, to the point of obsession. And the acquisition of parts of the Ottoman Empire after 1918 brought a different dynamic to the geopolitical map. He indulges a counterfactual fantasy that these parts of the Indian Empire would have ‘likely’ been part of India (or Pakistan) post-1947, and that South Asia could have been the beneficiary of the oil boom of the Gulf; this is wholly unrealistic.

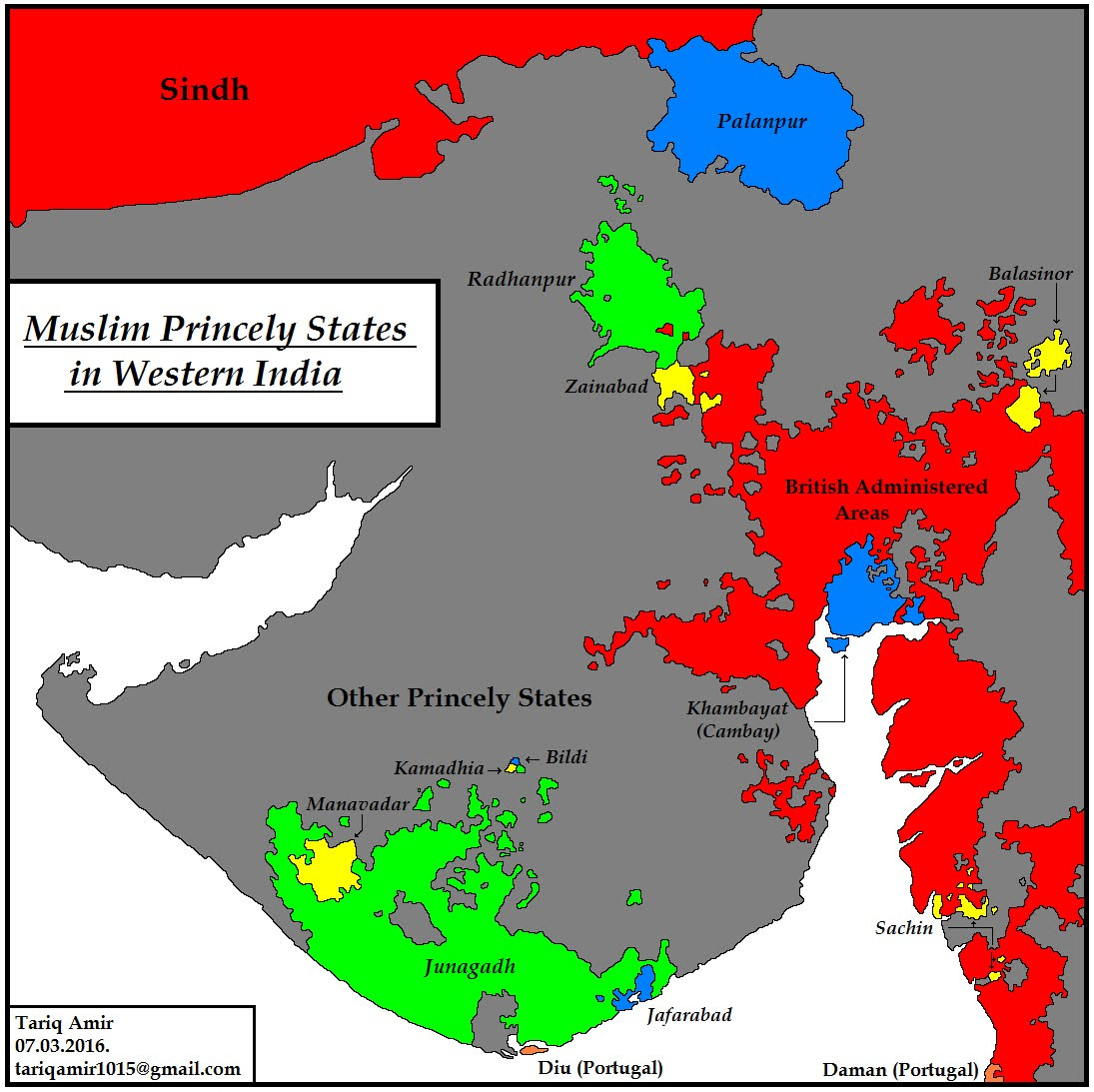

Skipping for a moment the ‘Great Partition’, his ‘fourth partition’, that of the princely states, rivals the Arab emirates for incredulity. Again, he is mired in legalism. The states notionally ‘became independent’ along with the India and Pakistan, although there were only a handful of cases where this was anything other than a mopping-up exercise: Junagadh, Jammu and Kashmir, and Hyderabad. Dalrymple is moon-faced and starry-eyed about the fate of these states as is possible for a liberal westerner to be; the reality is that neither of the successor states to the Raj, nor Britain itself, did anything other than quash the notion that independence was ever an option (certainly beyond J&K - and that was too strategically valuable for either India or Pakistan to let go). I mentioned maps earlier: perhaps it would have been valuable for the reader to be shown a map of Junagadh:

Portraying the absorption of nearly six hundred4 legally independent realms into two successor nations as a partition is just strange. J&K and Hyderabad were both referred to the UN Security Council; ‘In 2010, Hyderabad remained on the ‘list of matters with which the Security Council is seized.’5 Both were settled by force, not legalism. J&K was fought over, with the line of control being agreed between India and Pakistan becoming a de facto border. Hyderabad was unilaterally settled by force in four days, with by India proving that a functional army is more important than wealth or legal fiction. Significantly, the British government ordered British officers to resign from the Hyderabad army immediately before, in order for them not to fight against a Dominion.

Dalrymple has a tendency for preposterous statements, but this one (regarding his ‘fifth partition’) takes some beating: ‘In 1952 Bangladesh was no more inevitable than an independent Telegu-speaking state.’6 What is remarkable is that the idea of 1947-Pakistan could endure - split between East and West with nothing joining them except for their Muslim majorities, least of all land.

The narrative of the 1971 war is good, and unsparing, which makes the ‘fifth partition’ framing even more jarring. In particular, Dalrymple does not shy away from the rape campaign of the (West) Pakistan forces, including quoting a source that, ‘Bengali women were immoral and therefore fair game, because they didn’t wear blouses over their sarees’7, though of course without hinting at parallels with the ‘fair game’ rhetoric on UK shores. The remarkable post-war campaign of Mujib Rahman’s new administration to rehabilitate the victims of rape as Birongongas (War Heroines) is mentioned, but as a sideline. (Did any other state ever do such much for its rape victims, let alone a Muslim one?) More attention is given to Ravi Shankar and George Harrison’s ‘Concert for Bangladesh’, with the explicit message that the Pakistani Army had committed ‘undoubtedly the greatest atrocity since Hitler’s extermination of the Jews’8. Is this the earliest example of explicit Holocaust-mythologising?

The overall effect of the ‘Five Partitions’ framing is to dilute the impact of the central one, the ‘Great Partition’ of 1947. Whether he designs to or not, the tales of communal slaughter, from the Burma insurgency to the Bengali war, serve to mitigate the worst atrocities of them all, conducted mainly in the Punjab (and secondarily in Bengal) in 1947. Large-scale population exchanges in the wake of carving up a defeated empire are not unusual; nor are borders drawn on a map without adequate knowledge of the reality on the ground. Poor old Cyril Radcliffe probably did as good a job as he could have. What was scandalous was the headlong rush-for-the-door, the abandonment of responsibility by Mountbatten, only encouraged by Atlee’s government in London.

Dalrymple has a habit of sixth-form-psychologising the key participants in Partition, framed in caricature thumbnails. A young Jinnah, eloping with his Parsi bride, is shunned by Bombay society, and ‘having once dreamed a modern India would be able to move past divisions of religion and caste, Jinnah became disillusioned.’9 Nehru is ‘changed forever’ by sharing a train berth with General Dyer, days after the Amritsar massacre. Dalrymple updates Churchill, saying Gandhi ‘cos-play[ed] as a sandhu’10. And the intimacies of Edwina Mountbatten with Nehru, alongside her strange relationship with her husband, are not exactly groundbreaking research.

Between the flow of narrative history and the first-hand voices, the author is largely absent; but when he surfaces, his judgement is either specious or plain wrong. I’ve mentioned some earlier, but here is an example. In 1960, Pakistan, under the military dictatorship of Ayub Khan, and supported by Western pressure (and financial interests) had agreed the Indus Waters Treaty with India, which guaranteed a share of the tributaries of the Indus (the ‘five rivers’ that give Punjab its name) to Pakistan. Pakistan was in less favourable position than India, due to flowing through Indian-controlled Kashmir, as India had demonstrated in 1948 by impeding the Sutlej, damaging irrigation in Pakistan. Dalrymple portrays India’s annexation of Goa (a Portuguese colony) in 1961 as the cause of the rupture in seemingly good relations, provoking Pakistani concerns about Indian aggression elsewhere. A more realistic reading is that Khan, with Western protection, played along with rapprochement until the water deal was signed, and subsequently adopted a more aggressive position towards India, including support for insurgency of the Naga hill-tribes.

Dalrymple’s impeccable, if soft, leftism (who could doubt a boyish peace activist?) buys him the freedom to undertake what is essentially a re-framing of Partition as just one of a series of violent conflicts that could have been avoided if the participants had been just a little bit less nationalistic. The counterfactuals run through his narrative: it all could have been different; ignoring whether or not they are at all realistic. Partition (the real one) was so violent not because the wrong lines were drawn on a map, but because the British cut our losses as fast as possible, withdrawing people and troops headlong (by April 1947 there were just 11,400 stationed on a subcontinent turning hot). And the unspoken rule from both sides was: massacres are fine, just don’t involve any Westerners. (Dalrymple documents a rare exception to this: the murders of Catholic missionaries in Baramulla as the Pathan irregulars marauded down Kashmir. He ignores, however, the 20,000 slaughtered and 5,000 raped in one day in Mirpur, which I wrote about here.)

The Five Partitions framing posits unrealistic counterfactuals in the place of more serious questions. Barely mentioned is Ceylon, beyond being the base of Mountbatten during the War; far closer in history, culture, legend and sheer geography than Burma, but never administratively part of the Raj. Why? Would that have changed the dynamics of India post-independence? Could the Sri Lankan civil war have been prevented?

Neither does he consider a further crucial counterfactual from history - in fact, there is no evidence from the text that he is even aware of it. To what extent was first partition of Bengal under Curzon in 1905 (reversed six years later) the seed for the subsequent partition of India and Pakistan? It is a question that is surely central to Dalrymple’s narrative, and a better candidate to be considered a ‘partition’ than some of his others.

The biggest counterfactual of all is: could India have broken up? In many ways, the miracle is that the nation survived, and whilst Dalrymple does not claim to be a political commentator, some recognition of the political deftness of Nehru and Indira Gandhi over four decades is surely warranted. The scale of violence had (say) the Dravidian South sought to separate itself would surely have led to more millions of deaths and ethnic transfers. The author’s running antipathy to the ‘sacred geography of the land of Bharat’ is misplaced; it has played a role in the political formula of modern India, and kept the country remarkably peaceful.

To put it as simply as possible: given the post-independence histories of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma and Sri Lanka, what would one have predicted for India? The Partition That Didn’t Happen is the most interesting question of all.

This review probably wouldn’t be so critical if every other had not been so fawning; it’s mixed, and I’d rather have someone suggest a Big Idea even if it’s faulty, than have no ideas at all. But the question remains: why has this book been so hyped and so unquestioned? Is there more to see than a nepo-writer land on his young paws like the luckiest of cats?

Before considering that, some stylistic quibbles. For such a lavish publication, the lack of editing is apparent, leaving the text at times slapdash and clichéd. Is this good writing?

At the same time the Arabian Raj was hurtling into a new and unexpected future thanks to the discovery of a putrid, viscous, sticky, liquid: oil… An oil refinery soon dominated both Aden’s landscape and economy, accounting for a staggering 90 per cent of the city’s gross industrial output. It pumped life into Aden’s veins, contributing 10 per cent to its GDP and a staggering 75 per cent to its export earnings.11

‘Staggering’ stuff.

There are some remarkable slips of liberal assumptions and modernisms that the author (being charitable) probably doesn't even notice. ‘Institutional racism was woven into the fabric of life of the Raj', ‘Bose’s INA was a diverse and inclusive organisation’, Nasser ‘fought for social justice while also brutally quashing dissent’. The price of oil ‘skyrockets’, a Bollywood hit ‘goes global’, and things are ‘protested’ in the American usage. Some participants in the tale come with constantly repeated epithets as though the author has no courage that we will remember who they are otherwise: ‘half-paralysed Phizo’, or ‘chain-smoking V.P. Menon’.

The net effect of ‘Shattered Lands’ is something approaching Raj nostalgia. Nostalgia for the ‘undivided’ empire where communal peace was, largely, kept; religious traditions could be syncretic rather than reactionary; and nasty ‘nationalisms’ were held at bay. And nostalgia for the glamourous world of Maharajahs and Nawabs, the conservers of wild lions and patrons of musicians cruelly betrayed by the British.

It is, though, an account where the Brits get off lightly - particularly in the Partition itself. It’s hard not to think that a Dalrymple can get away with things in the liberal world that a Nigel Biggar could not. But more interesting than the nepotism is the question of whether the book’s reception tells us something wider, whether our relation to Empire and its end is changing.

One possibility is that the national self-flagellation over Empire has peaked - at least if you accept the mantra of institutional racism, social justice, anti-nationalism.

Another is that demographic changes in the UK itself are leading to a re-creation of the conditions of the Raj, but this time at home. The premise is of course false, given the uncomfortable inclusion of native Brits in the mix; but it is maybe a priming that the state has some institutional memory of how to manage such a system (recently, in the case of Northern Ireland): what I have called Milletisation elsewhere, although Communalism would be more apt in the context of our Indian legacy

A darker possibility is that tales of violent ethnic conflict which that are unleashed feed the ‘civil war is coming’ narrative, promoted recently by the King’s College Professor of War Studies, David Betz (and amplified by too many on the ‘right’). The book ends:

The last decade has witnessed the decline of globalisation, the strengthening of borders and the resurgence of nationalism across the world. India’s Partitions are a dire warning for what such a future may hold.12

An alternative conclusion would be that mass population transfers are a norm of history, not an exception.

Thanks are due on this, and many other points I mention here, to someone who would do a much better job of reviewing this book.

‘Shattered Lands’, pp 72-73

Ibid, p 84, p 72

It is striking that the exact number is not quantifiable

Snedden, “Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris”, p 152

‘Shattered Lands’, p 291

Ibid, p 384

Ibid, p 390

Ibid, p 13

Ibid, p 14

Ibid, p 294

Ibid, p 430

The book does seem rather nostalgic about the Raj. This wasn't a fawning review though. https://observer.co.uk/culture/books/article/the-partitions-that-made-modern-asia